15% Discount on books, cards, and art from my online store.

No worries!! I'll only send occasional updates. And I promise to never share your email address with anyone for any reason.

No worries!! I'll only send occasional updates. And I promise to never share your email address with anyone for any reason.

The appearance of spring in the front range of Colorado is erratic: blue skies and sixty-plus degrees one day, a foot of snow and below freezing temperatures the next. Yet somehow a variety of creatures brave these extremes and inform us, whatever the day’s weather, that spring has indeed arrived. The return of Western Bluebirds is one welcome sign that spring has returned. Another is finding the first flowers in bloom.

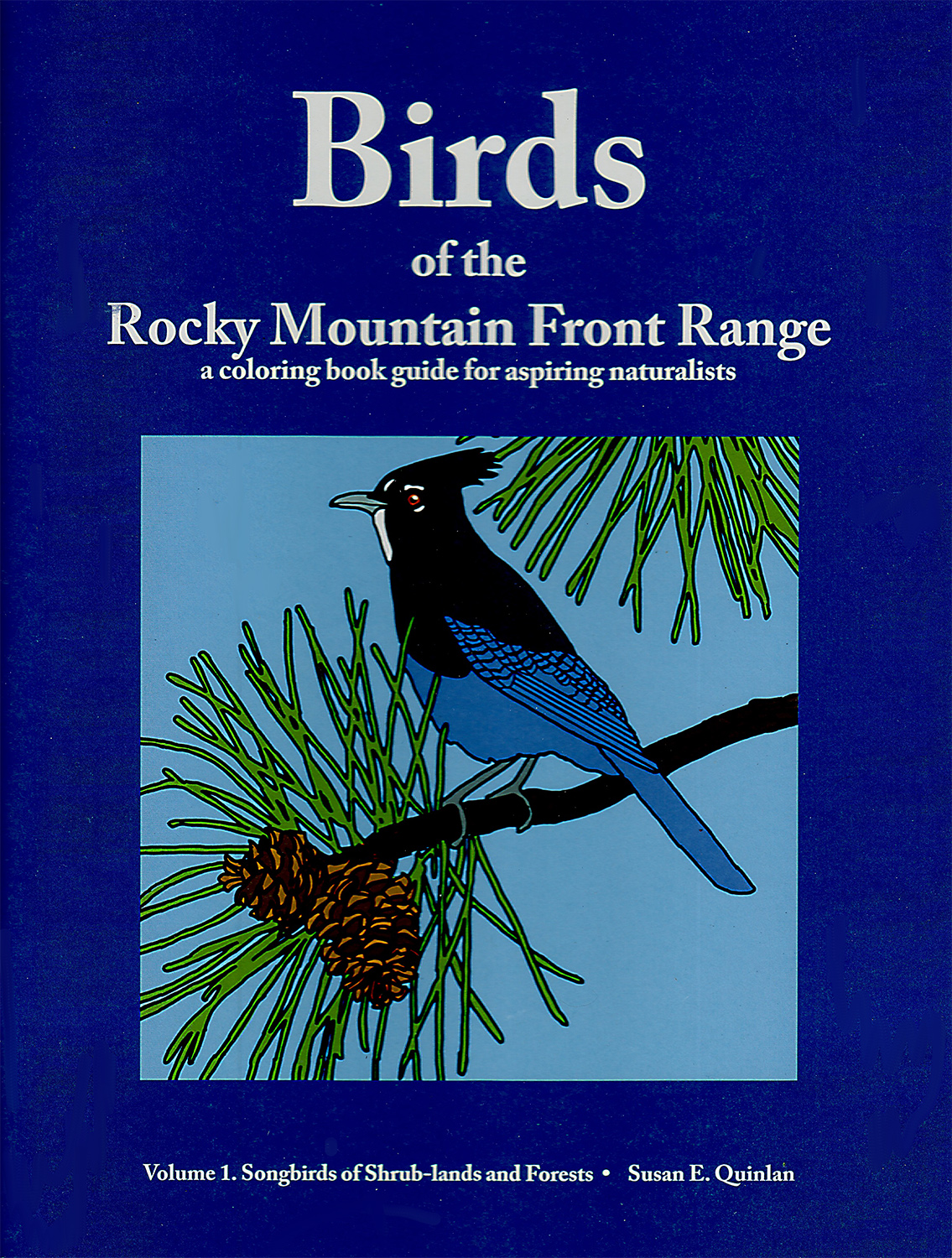

I discovered the first spring blossoms of the year on a south-facing hillside of our front range property on March 26, a few days ago. Three separate Nuttall’s violet (Viola nuttallii) plants had pushed out dainty yellow flowers in the warmth of that beautiful sunny day.

While reflecting happily about finding these early spring flowers, some questions came to mind: Why are they called Nuttall’s violet? What pollinates their flowers so early in spring? Do they rely on mycorrhizal fungi to obtain minerals from the soil? Are their seeds dispersed by ants like those of other violet species? Are the plants edible? Poisonous? What kinds of animals eat their leaves?

With the covid-19 virus “shelter at home” lockdown quarantining me in place, now seemed a good time to get better acquainted with the Nuttall’s violet. I decided to investigate. My first inclination to begin getting to know these violets better was to do some sketches of the flowers and leaves. But the next day dawned gray and very cold. I had to search carefully to even find the tiny plants again because the bright flowers were closed against the cold and difficult to spot.

Violets encased in ice on a cold day in late March.

Sketching could wait. Back inside, I hunkered down to avoid the cold, gray day myself. First, I thumbed through some of the books in our library then searched out a few journal articles via the online library at CSU. I soon began finding answers to some of my questions.

Nuttall’s Violets are named after Thomas Nuttall, a British born naturalist who explored and studied nature in the western United States in the early 1800’s. That answer was easy to locate.

In contrast, I wasn’t able to find any specific information about what pollinates Nuttall’s violets. Botanist Peter Bernhardt, writes in “Wily Violets and Underground Orchids” that violets produce long-lived flowers that are “remarkably resistant to periods of freezing.” He further states that violets change their flower positions and move their petals to facilitate visits by a diverse array of insects. According to various references, other species of violets are pollinated by a wide variety of insects, including sweat bees, mason bees, bumblebees, wasps, sawflies, overflies, dance flies, hoverflies, hawkmoths and butterflies. However, the authors of the informative Boulder County Nature Almanac opined that Nuttall’s violets likely self-pollinate because they open early in spring before many insects have emerged.

Note the deep purple nectar guides of the Nuttall’s Violet flower as well as the lanceolate leaves which differ from the characteristic heart-shaped leaves of many other violet species.

This information made me wonder; How long-lived are Nuttall’s violet flowers? Do these violets change their flower positions or move their petals over time? I also wondered why these small plants would put so many resources and so much energy into producing relatively large bright, showy flowers, complete with deep purple nectar guides, if they rely mainly on self-pollination?

Further firsthand observations of the violets seemed a possible way to find some answers. I resolved to carefully examine several individual plants and flowers over the next few days to see if I could observe any insects visiting the open violet flowers.

When the sun came out again on Saturday, I first spent over an hour searching carefully around our hillside for active insects. I found three different kinds of grasshoppers, one medium-sized orange butterfly, one tiny ant, and a couple of small flying insects of unknown identity. Clearly some insects are active at the same time that Nuttall’s violets are blooming.

I then sat down near some violets and attempted to watch the open flowers for two, ten-minute sessions just to see if I could spot any flower visitors. Nope. I didn’t hear or see any insects around the plants at all, but I also found it tough to keep my eyes trained on the flowers. I resolved to try watching the same flowers again for a longer time period another day.

On Sunday I ventured out again with my sketch pad and a couple of pencils. I noted that some of the flowers had remained open and fresh looking for at least three days now, but a couple that had been open the first day of my observations were now closed and shriveled. Some of the still-open flowers had changed certain petal positions slightly, but for the most part the flowers that remained open remained in positions close to those I had observed earlier.

With some difficulty, I managed to get my nose right down next to flowers on several plants so I could sniff them as I wondered if they had a detectable violet scent. I got one whiff of a sweet scent near one plant, but I couldn’t smell anything near any of the other plants I sniffed. I later discovered a possible reason for this. According to Wikipedia the scent of some violets contains a compound which “temporarily desensitizes the receptors of the nose, thus preventing any further scent being detected from the flower until the nerves recover.” Curious! I need to do some more sniffing–if I can manage to get down that close to the tiny flowers again!

Sketching allowed me to pay close attention to the flowers and watch for possible pollinators for a longer period of time.

With my mind focused on the plants to enable careful sketching, I found keeping my eyes trained on the flowers was a lot easier. I managed two half-hour observation/sketching sessions. Still I observed no flower visitors, though I did hear two small insects buzz past in hurried flight somewhere.

Obviously lots more observation time will be required to determine, by watching alone, if the early flowers of Nuttall’s violets ever attract any insect pollinators. This might be a good outdoor activity during the Covid-19 quarantine, but I really need to find out if pollination biologists have any better methods for identifying pollinators than simply watching to see what might visit the flowers! Surely they have some better techniques. For now, I think the answer to the question of whether insects visit and pollinate the early-blooming Nuttall’s violet flowers awaits further research.

One of my sketches of a Nuttall’s Violet in bloom.

Nuttall’s violets are a well-known and widely distributed species occurring from southern New Mexico to central Canada. Thus you might think this species’ pollinator(s) would already have been determined. Not so. Many basic facts, like what pollinates particular flower species, remain as yet unanswered.

Back to reading. Apparently all violets do self-pollinate! However, self-pollination definitely occurs not in the bright showy flowers like those I sketched, but rather in separate, later-blooming, greenish flowers that emerge only under the leaves, or possibly underground. Who knew? Violets bear secret flowers!

Violets have “cleistogamous” flowers.

Scientists call these hidden, self-pollinating violet flowers: “cleistogamous,” or “cryptic” flowers. “Cleisto-” is from a Greek root word meaning “closed.” These unusual and differently-shaped violet flowers lack petals and never open. I searched but wasn’t able to find any of these on the violet plants I examined in the last few days. But it is still early spring. I need to look again in a week or two as the cryptic flowers appear later, and may be not only under the leaves but also underground – at least according to some sources.

I wasn’t able to find any specific information about Nuttall’s violet and mycorrhizal fungi either, but most plants in the violet family are included in the 85% of vascular plants known to have a mutualistic association with fungi. It is dry and hot here in summer so I rarely find any mushrooms. But maybe these violets associate with truffles (a sort of underground mushroom) or perhaps if I look more often and more carefully during wet periods, I will find more mushrooms in the areas the violets grow.

I expect to have quite a bit of time for observation of nature during our forced quarantine this spring. So I am going to be looking not only for the cleistogamous violet flowers I just learned about but also plan to keep a close watch for possible pollinators. I am going to search more carefully for mushrooms. And I plan to make a special effort to observe these violets as they go to seed.

My watercolor painting of Nuttall’s Violet based on one of my pencil sketches.

Violets have a surprisingly complex method of seed dispersal. Their tiny seeds grow inside elongated capsules which gradually dry out and shrink. At a certain point, the dry pods split apart and explosively cast out the seeds like tiny cannonballs. The seeds shoot out to land a few centimeters away from the parent plant. However, the story of violet seed dispersal doesn’t end there.

Violets produce seeds that have a small oily or fatty glob attached at one end. This glob, called an “elaisome” emits an odor that attracts certain kinds of ants. The ants typically drag the seeds back to their nests where they usually eat all or some of the fat body (which is usually rich in nutrients), then cast the remaining, still intact seed, into their waste heap or somewhere nearby.

The association between certain plants and seed-dispersing ants is called myrmecochory.

About four percent of flowering plant species (about 11,000 species) worldwide are entwined in known myremecophenous relationships with ants. Such associations are generally considered mutualisms – that is a kind of symbioses where both involved species benefit. The ants appear to benefit by the nutrition acquired from the elaisomes, while the plants benefit by getting their seeds more widely dispersed. Seeds carried off by the ants are less likely to be eaten by seed-predators such as rodents, and are likely to end up in a more nutrient-rich soil where they may be more successful germinating and surviving.

While most myrmecophenous associations may be mutualisms, there are some known exceptions. Certain plants produce seeds with elaisomes that contain few nutrients but give off pheromones which smell like ant larvae or ant corpses and trick ants into carrying the seeds back to their nests.

Interestingly, the specific association between Nuttall’s violets and ants has been studied in some detail in Colorado at the Rocky Mountain Biological Research Station by Christine Turnbull as reported in her PhD thesis at Northwestern University. Turnbull found two different species of ants gather and disperse Nuttall’s violet seeds: Mvrmica discontinua and Formica podzolioa. She concluded the ants do reduce the number of violet seeds eaten by various rodents.

I am curious to find out if the same species of ants occur here and might pick up and disperse the seeds of the violets on my hillside. I am not an expert at ant identification, but these days, it is easy for anyone who is interested to obtain some expert help with insect identification. If I eventually find an ant carrying off a violet seed (and can take some halfway decent photos), I know I can get some help with species identification at: i-naturalist and/or bugguide.net

While wondering about the connections between Nuttall’s violet and other inhabitants of the front range foothills ecosystem, I wondered first about pollinators since the flowers were blooming. And I thought about seed-dispersers because I already knew about the interesting myrmecophenous relationships between ants and other kinds of violets. Next I wondered what animals eat violets? Are the flowers or leaves eaten by deer? Wood rats? Meadow voles or white-footed deer mice? Might there be any insect larvae that feed on Nuttall’s violets? With some brief searching through various references, I didn’t learn all the answers to these questions but I did learn some interesting information which further increased my curiosity.

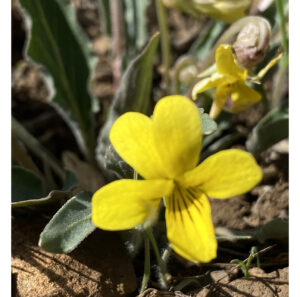

Wild turkeys (like this one I photographed in my yard last year) eat the tuberous roots of some violets. Perhaps the roots of Nuttall’s Violets are part of their diet here?

Martin, Zim and Nelson’s classic guide to North American wildlife food habits lists cottontail rabbits as the only known vertebrate consumer of violet leaves. They note wild turkeys eat the tuberous roots of some violets and list a few kinds of birds and mice known to eat violet seeds. Turnbull reported that, in her study area, Viola nuttallii seeds are eaten by deermice (Peromyscus manlculatus), western jumping mice (Zapus princeps), chipmunks (Eutamias minimus), and golden-mantled ground squirrels (Spermophilus lateralis). Of those, I am only certain that deermice occur on our hillside; western jumping mice and chipmunks are possible, but so far I have not observed either. Might these seed-eaters possibly eat the leaves of the plants too? I noticed a few of the leaves of some of the violets I examined had been bitten off or had pieces chomped out of them, so I know something small eats Nuttall’s violet leaves—just not exactly what.

Many violets are reportedly edible to humans. Sugared violet flowers are even sold as a special treat or cake decoration in Europe. Regarding the edibility of Nuttall’s violet, however, the authors of Colorado Nature Almanac* indicate they are reportedly “purgative,” meaning they have a strong laxative effect. That suggests Nuttall’s violets may contain some poisonous compounds.

In my search for additional information about what might eat Nuttall’s violets, I was surprised to learn that the entire violet plant family (Violaceae) is known for producing poisonous “cyclotides,” an unusual and fairly recently (mid-1990’s) discovered group of circular proteins produced naturally by certain plants and microbes.

Curiously tangled and often quite poisonous, some cyclotides are cytotoxic—meaning they kill cells, some are hemolytic–they break open blood cells, others are antibacterial, others antiviral, insecticidal, antihelmintic, anti-tumour, and possibly anti-lots of other harmful things from HIV to breast cancer. Cyclotide poisons are thought to be a violet plant’s defense against insect and fungal enemies. Some of the cyclotides produced by violets are known to specifically inhibit the growth and development of Lepidopteran caterpillars.

Tissue from every species of the violet family that has been tested so far seems to contain cyclotides of some sort and each species contains unique versions.

As far as I could determine, no one has as yet tested Nuttall’s violets. Perhaps someone needs to study the chemistry of Nuttall’s violets more carefully. We find ourselves seriously in need of some new antiviral compound these days! About 75 percent of pharmaceutical drugs humans use are derived from chemical compounds produced by plants. Tropical plants are considered the most likely source of potential new medicinals – and lots of violets occur in the tropics. But it seems the tiny yellow violets growing right here in my Colorado yard might be producing as yet undescribed and highly unusual and potentially medicinally-valuable proteins. I must leave further investigation of this topic to a chemist. But knowing about their potential toxicity, I became more curious to learn more about what animals might be eating them.

A bit more researching using the terms: “violet” and “host plant” turned up some information about the prairie violet, (Viola pedatifida) and its importance as the host plant for the endangered Prairie Fritillary butterfly (Speyeria idalia). This now rare butterfly species once occurred across much of America’s great plains.

One of the Fritillary Butterflies that frequents our hillside. (Digital painting)

Reading that, I wondered if Nuttall’s violets might be a host plant for any of the fritillaries I see around my hillside later in summer. I found the answer to that question on The Colorado Front Range Butterflies website. Violets are the known host plant of several local species of fritillary butterflies. Viola nuttallii is the identified as the specific host plant of Edwards’ Fritillary (Speyeria edwardsii) and also the Coronis fritillary (Speyeria coronis).

These and some other fritillary species overwinter as caterpillars. Might these caterpillars be the leaf munchers which had grazed on some of the violet plants I examined? Despite a careful search, including the undersides of many leaves, I wasn’t able to find any caterpillars. I will have to keep looking.

Noting that fritillary butterflies are bright orange in color suggests to me the possibility they might be aposemitic—that is, their bright colors might be signaling potential predators that they are unpalatable or poisonous. Monarch butterflies are an example of a well known aposematic species. A Monarch caterpillar garners poisons from the milkweed plants it feeds on; these poisons are retained when the caterpillar metamorphoses into an adult butterfly. Interestingly, fritillaries are in the same family of butterflies as the Heliconia butterflies of the tropics—that group is renowned for many species whose caterpillars feed on poisonous plants and adult butterflies with bright aposematic coloration. Might fritillary caterpillars not only consume, but also store the toxic cyclotides produced by violet leaves? I did a bit of journal and internet searching on this topic, but so far have not found any research on fritillaries and violet cyclotides. Hmm. Another question in need of much further research.

When I decided to learn just a bit more about the first spring flowers in my yard, I didn’t expect my learning journey would take off quickly in so many directions. Through observations, some reading, a bit of literature searching and some web-surfing, I learned a surprising amount about these tiny flowers that herald the return of spring. I learned some history, added a few new words to my vocabulary: (cleistogamy and cyclotides), learned a bit about chemistry, discovered that ten species of fritillary butterflies occur right here in my county (no wonder I haven’t been very successful identifying which species I’ve seen), became more interested in learning to identify specific ant species, and concluded that as yet, which, if any, insects pollinate Nuttall’s Violets remains a mystery.

I am amazed at how much scientists know, and yet how much remains unknown and unresearched. I am both frustrated and excited by how much I still have to learn. So much about nature remains to be investigated and discovered! Start with a small flower. Start anywhere. Nature’s interconnections will eventually lead you everywhere.

A little spring flower has reminded me, once again, that nature is amazingly complex and endlessly fascinating.

Click here to read an interesting blog about Violets in Maine.

Click here to view a video and some photos of a different violet species shooting its seeds. (I’d like to see if I can capture this happening with Nuttall’s violets later in the season.)

Boulder County Nature Almanac: What to See Where and When. Ruth Carol Cushman and Stephen R. Jones with Jim Knopf. Pruett Publishing Company. 1993.

Colorado Nature Almanac by Stephen R. Jones and Ruth Carol Cushman. Pruett Publishing Co. 1998

Wily Violets and Underground Orchids: Revelations of a Botanist. Peter Bernhardt. William Morrow & Company. 1989

The Dynamics of an Association Between Viola nuttallii Pursh and its Seed Dispersers Myrmica discontinua and Formica podzolica Francoeur. Christine Turnbull. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 1985

American Wildlife & Plants: A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits. Alexander C. Martin, Herbert S. Zim, Arnold L. Nelson. Dover Publications. 1951.

Distribution of circular proteins in plants: large-scale mapping of cyclotides in the Violaceae. Robert Burman, Mariamawit Yeshak, Sonny Larsson, David Craik, K. Johan Rosengren, Ulf Goeransson. Frontiers in Plant Science. Vol. 6 Article Number: 855. 2015.